outer voice: kinds of time

March 22 – April 7, 2024

Curated by Jason Le and Outer Voice

claire barrera

Roland Dahwen

Erin Boberg Doughton

Rubén García Marrufo

Sarah Rushford

Ash Stone

Qi You

Reception Saturday April 6, 2024 5pm – 8pm

Performance Program Saturday April 6, 2024 6pm Featuring claire barrera Will you with me? and Qi You Blockwalking and more. Please wear mismatching shoes to partake in Blockwalking, we will have some extras.

The exhibition is funded by the Ford Family Foundation

Themes in Outer Voice: Kinds of Time include the experimental telling of immigrant, mixed-race, and queer experiences, the voices of mothers addressing invisible labor, re-examination of communication, the challenging of hypercapitalism, the necessity of play, and the inseparability of art and life. Underlying these themes is the group's exploration of the notion that time can be perceived differently through each of the works.

FOR: OUTER VOICE - KINDS OF TIME

by jason n. le

During their inaugural season this past year, the Outer Voice collective has accomplished the poetic feat of dialoguing with time. Put another way, Outer Voice’s first cohort – claire barrera, Roland Dahwen, Erin Boberg Doughton, Rubén García Marrufo, Sarah Rushford, Ash Stone, and Qi You – have welcomed time as their honorary eighth member, with distinction. And its presence is evident: the members of Outer Voice have demonstrated through their works that employ movement, video, performance, action, ephemera, and artifact that time is a welcome force, a mysterious omnipresent being, and a malleable material.

When Outer Voice asked me to advise the curation of their most recent show, Kinds of Time, admittedly, one of my initial reactions was, “Wow, this is a lot of video work.” Now, let me be clear that my reaction had no negative intentions whatsoever – I hold a deep love for video work, which means that I, more often than not, will sit and watch them in their entirety when exhibited in museums and galleries, no matter how long they may be (apologies to any past and future gallery-hopping friends). Reflecting on it now, my startle didn’t come from a surprise at the presence of video work or the quantity of it to be organized for exhibition with a limited amount of wall space or technology. What caught me off guard was thinking about it in relation to Outer Voice’s mission statement: to provide space for a supportive community of artists working with time-based media.

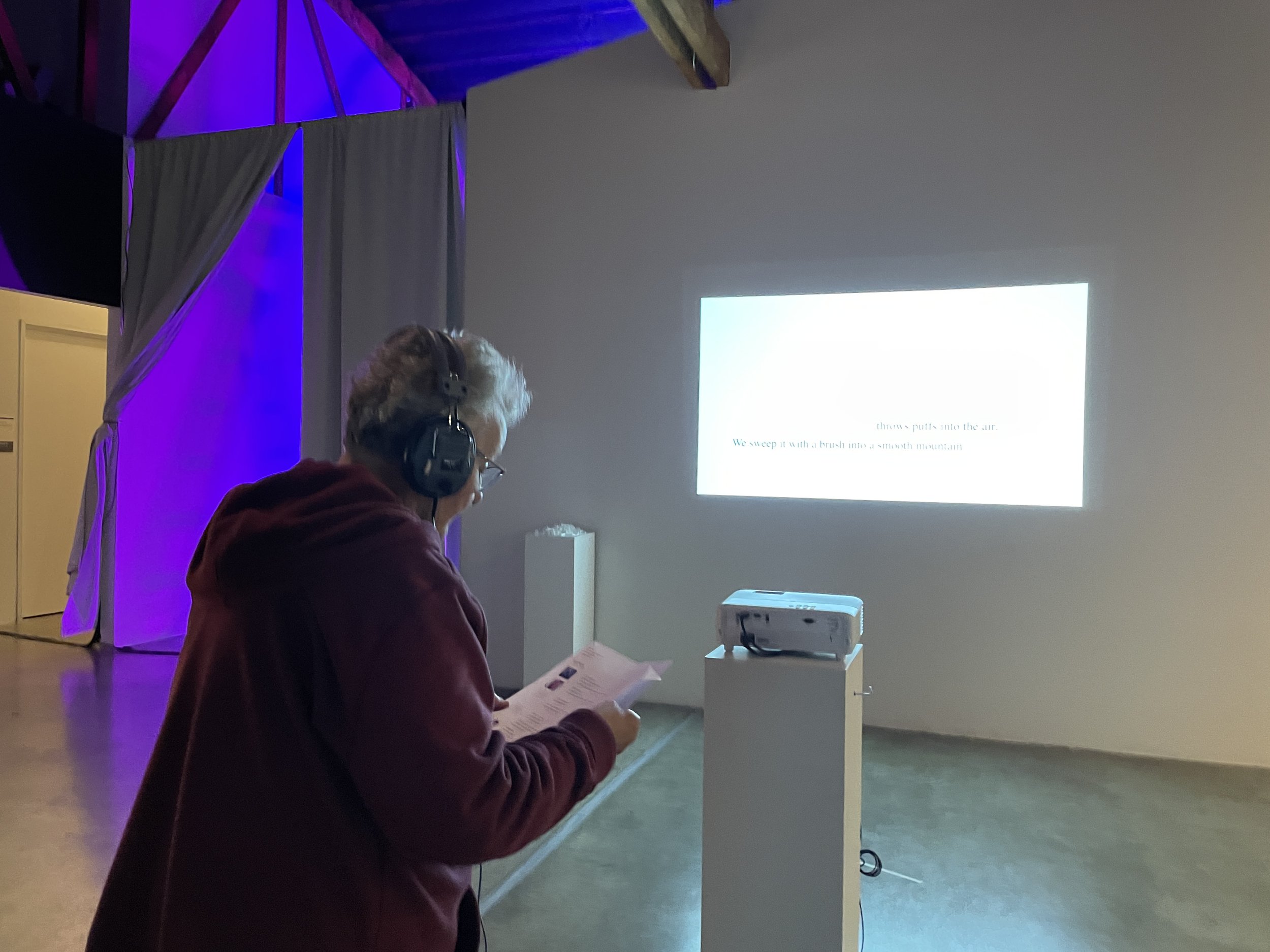

“Blockwalking II” performance by Qi You

“Will you with me?” performance by claire berrera

“Body double” performance by Erin Boberg

Time-based media as a mode of art practice still sits in a contentious realm. That is, I believe people are still trying to figure out exactly what it is, how to read it, and what to do with it. Is it performance? Video? Installation? All of the above? How does it get installed? How does it get preserved and archived? As far as I am aware, no wings exist yet in any museum that are dedicated specifically to time-based art (if there are, please prove me wrong and send them to me!). Where does time sit amongst the hallowed halls of painting and sculpture from days past? Maybe its invisibility is due to its status as the enemy of the museum itself, which premises its core function on the idea of freezing time: suspending works of art in a temporal no-person’s-land for the sake of forever future consumption. (Which is ironic, in a way, considering that such a tactic holds potential for being a time-based practice itself – stopping time, truly ignoring it, rather than letting it run its course.)

Maybe a better way of explaining time-based media’s invisibility is precisely to return to the impossibility of describing time as an artistic medium or material to work with. (What do you mean your work is “time-based”?) Some artistic approaches fold time into the work more obviously than others – things like durational performances, temporary installations, and disintegrating or dissolving sculptures, to name a few examples. But – at the risk of opening a can of worms – what even is time’s relation to these creative approaches? Is evidencing the unstoppable march of time the ontological marker of time-based art itself? Or does time-based art become itself when an understanding of orderly time as an immovable force is set aside, and we allow time to become a malleable, amorphous material to be reshaped and manipulated?

Video art, then, is time-based media not in the way that one expects it to be, in that it occupies a certain length of time, as the scrub bar on any given media player tells you so: there is a finite beginning, duration, and end. Rather, video art is time-based media in its ability to create its own temporal space independent of what exists around it. Or, better yet, the time-based nature of video art is its innate ability to take you out of your own time and relocate you wherever (whenever) it has created for itself.

But let me emphasize that this is not an essay just about video art, although the modality is so good at marking time. This is an essay about time, or rather the odd force of time, or maybe actually the absurdity of time, or really how the structure of time shows its fragile underbelly when employed as an artistic material. Taking on the task of creating time-based work is more than articulating a creative representation of an immovable and uncaring force, it is sidestepping what one generally understands as reality to offer another reality.

And that is precisely what Outer Voice did with their season. Their work demonstrated that time is not a bullying force that bowls us over. Kinds of Time harmonized projects that expose the flexible boundaries and malleability of time itself, illustrated by Dahwen’s video almanac of “natural” plants that are actually plastic replicas of their referents, by the trace of a past dinner party full of magic tricks and warm food hosted by Doughten, or by Stone’s casts of her own face made from cheese, an eerie double-entendre of preservation through shelf-stability and allusion to death masks. Other works like Rushford’s alternative reading approach to a paragraph of text or barrera’s examinations of inter-generational knowledge exchange disrupt the comfortable linearity we expect of time. And Marrufo’s video assemblage or You’s score to walk a block in someone else’s shoes push viewers to think of elsewhere and otherwise, suspending our spatiotemporal standards.

The other day, a colleague of mine returned from a recent trip to Italy. She was there to see some art, eat some gelato, and take in the historic sites that amazingly still stand to this day. As I listened to her recount her travels, of walking across bridges that led from palaces to prisons that she had studied in her undergrad, she gifted me a souvenir: a pin with a text equation that read “PAST + FUTURE = PRESENT.” If the present (the specific now that we inhabit) is comprised of the past (that which has already happened at some point) combined with the future (that which may or may not happen at some point), then what is the temporal space of the present if not a jumbled mix of open-ended possibilities and interpretations? It can be everything and nothing. Why did you read this essay in the order that you did?

Jason N. Le